This was a letter/suggested blog post sent to the IJFAB blog in response to its recent conflict with Shelley Lyn Tremain. I think that Tremain showed courage and sound judgment when she admonished IJFAB not to publish work from bioethicists who are using their platforms to create expansive PAS regimes. It’s not appropriate for feminists or anyone else to take a neutral position on disabled people’s right to suicide prevention or sit quietly while countries use euthanasia to cut healthcare costs, so I think that Tremain did the right thing. I realize that framing bioethics discourse and PAS advocacy as sexual violence is controversial, but I think that rape is a legitimate metaphor for what mainstream bioethics and the PAS movement has done to the disabled community.

Here is the body of the reflection:

When I was growing up, people would walk up to me without warning and announce that I was “a retard.” They also not only said that they hoped that I would die, but described the ways that they would like to make that happen. Pretty much every day was a torrent of verbal and emotional abuse, right in front of teachers and other adults who decided not to intervene. The trauma from these experiences-which were intense and lasted for years-still impacts me as an adult. Sometimes it’s difficult for me to trust people in general, I am often waiting for them to do something cruel. Moreover, this expectation of mistreatment isn’t paranoia; as an adult I really have experienced oppression, bullying and abuse because I am disabled.

Mainstream bioethics is basically this experience on steroids. The philosopher kings and queens in charge of this field have no shame-advocating for eugenics,[ms1] saying that we should take seeing-eye dogs away from people in the name in the name of fighting world hunger[ms2] , and repeatedly telling disabled people to kill themselves[ms3] . I studied this movement between the years of 2007 and 2016, and although those studies lead to a great publication [ms4] opportunity, I really think that that research was bad for my mental health. I’ve read research postulating that sometimes historians are traumatized by historical events that they study, and I think that that’s true. [ms5]

After I was exposed to his ideas in a college philosophy program, I studied Peter Singer’s writings intently. I studied utilitarian ethics. I studied the history of the eugenics movement, infanticide, euthanasia, and stories of caretakers who had murdered[ms6] their disabled charges. Mart Pernick’s book The Black Stork[ms7] , which traces the American roots of the Nazi eugenics and euthanasia program, is one of the most disturbing books I’ve ever read. I read information about legislators in the 1910s trying to pass laws that would allow people to electrocute disabled babies. My K-12 education had held Helen Keller up as an example for disabled students to emulate, and Pernick’s book established that she was a quintessential example of lateral ableism. Despite being severely disabled herself, Keller strongly supported both eugenics and compulsory euthanasia-to get rid of people with cognitive and developmental impairments. . If Keller were alive today, she would be on TV, telling a news reporter that she supports PAS-and she would be functioning as a token, using her privilege to foment oppression against other people with disabilities. All of these revelations together-the comparing disabled people to chimpanzees, the proposals to electrocute disabled babies, and learning about historical oppression of disabled people that had somehow been omitted from the K-12 history curriculum- made me feel deep revulsion. I felt sick to my stomach, like when bullies took me into the woods, hit me with a plastic baseball bat, and dumped swamp water over my head.

It makes me feel even more revulsion to learn that some advocates for physician assisted suicide get a sexual thrill from helping people kill themselves. Lonny Shavelson, who is helping lead a lawsuit attempting to bastardize the Americans with Disabilities Act, has produced materials asserting that someone’s death is the most “intimate” experience that someone can share with them-more than birth, weddings, and sex[ms8] . Similarly, physician assisted suicide practitioner Phillip Nitsksche has asserted that after helping people kill themselves in the 1990s, he experienced an urgent need for sex. [ms9] That’s really disgusting, and it speaks to the reality that for some PAS proponents, trying to pass laws that help disabled people kill themselves, or helping them die by suicide, is functioning as a kind of porn. In other words, in some contexts, PAS is an act of sexual violence.

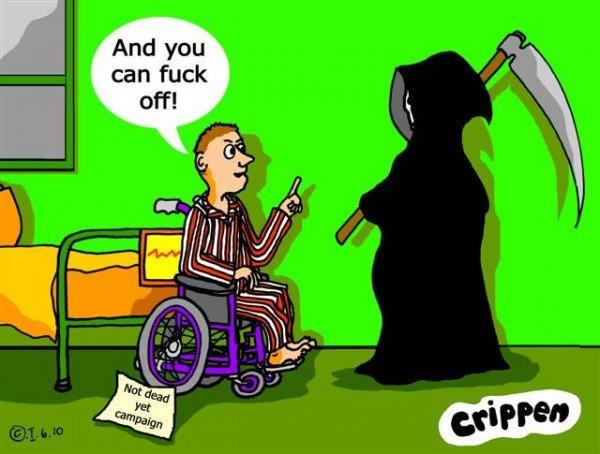

And, the proponents are bound and determined to pass these laws, no matter how many times the disability justice movement says “no.” That’s like rape. Mainstream bioethicists and and PAS advocates have demanded that disability rights activists and disability studies scholars engage them in a nice, polite discussion about killing disabled people. For the mainstream bioethicists, it’s all pleasurable intellectual masturbation. Well, disabled people are not sex toys. Multiple disability studies scholars have tried to explain why the field of bioethics routinely advances abhorrent ideas, and bioethicists continue to do it anyway. Hence, he disability justice movement owes no more respect to the mainstream bioethics movement that we would to a rapist.

As far as I am concerned, all of the bioethicists who compare disabled people to animals, or fetuses, or advocate taking services away from disabled people to solve world hunger are evil. Those philosophers who work hard to create a world in which disabled people are routinely killed or told to kill themselves have earned a special place in Hell; that’s where their scholastic activism belongs. I’m not suggesting that people use violence to oppose physician assisted suicide-that would lead to all sorts of other social problems-but I think the time for restricting ourselves to polite discussion has passed. Disabled people aren’t walking, wheeling philosophical questions for bioethicists to exploit to further their illustrious academic careers. We aren’t serfs who have to agree to die so that more privileged people can have total control over their bodies all the time. PAS proponents are not entitled to change our medical system into one in which doctors routinely offer suicide to disabled people and hence subject us to routine psychological violence-so that they can avoid suffering at the end of their lives.

And, all of this goes to the issue of IJFAB’s decision to publish Downie’s work. Tremain was absolutely right to call the journal out and hold it to account for giving a platform to someone who has made it her life mission to help disabled people kill ourselves. In deciding to give people like Downie a platform, JFAB is continuing in a disgraceful tradition of eugenic feminism[ms10] , a movement that ought to have ended with the eugenics movement in the 1930s. According to the aforementioned Pernick book, that’s what feminists at the time did-debated whether killing disabled people would further feminist goals. It’s 2022. IJFAB should know better than to facilitate that kind of discussion.

So, I stand in solidarity with Shelley Lynn Tremain. Impugning the decision to publish Downie’s work, and to hold IJFAB accountable for that choice, was the right thing to do. Standing up to IJFAB in that way must not have been easy for Tremain, but her decision to do that is an example of someone putting justice and fairness ahead of their career. Bioethics is a field that is premised on respectability and prestige, so much so that its privileged leading thinkers have become used to being to say and do whatever they want. They’ve come to expect obsequious paeans to their sagacity, no matter how abhorrent their proposals are. Facilitating that process-which is what is done when IJFAB publishes their work, is not ethical. Bioethicists who debate killing disabled people and participate in passing laws that result in a human rights crisis for people with disabilities are not entitled to have their Philosopher Queen intellects stroked by publication in a prestigious academic forum. They’re not entitled to have colleagues signal what fine, upstanding intellectuals they are. When JFAB publishes bioethicists like Downie, Udo Schuklenk, and other PAS advocates, the journal is normalizing discourse that tells disabled people to kill ourselves. It’s normalizing suicide, hate speech, psychological abuse and sexual violence. And that’s not ok.

[ms1]Can ‘eugenics’ be defended? | SpringerLink

[ms2]Peter Singer and the Ethics of Effective Altruism – Prindle Institute

Effective Altruism and Disability Rights are Incompatible | NOS Magazine

[ms3]Treatment-resistant major depressive disorder and assisted dying – PubMed (nih.gov)

[ms4]Anxiety Muted: American Film Music in a Suburban Age – Kindle edition by Pelkey, Stanley C., Bushard, Anthony. Arts & Photography Kindle eBooks @ Amazon.com.

[ms5]Can Historians Be Traumatized by History? | The New Republic

[ms6]2022 Anti-Filicide Toolkit – Autistic Self Advocacy Network (autisticadvocacy.org)

[ms7]The Black Stork: Eugenics and the Death of “Defective” Babies in American Medicine and Motion Pictures since 1915: 9780195135398: Medicine & Health Science Books @ Amazon.com

[ms8]A Chosen Death: The Dying Confront Assisted Suicide: Shavelson, Lonny: 9780684801001: Amazon.com: Books

[ms9]Damned If I Do Autobiography of Philip Nitschke (exitinternational.net)

[ms10]Catapult | Give Disabled Feminists the Respect They Deserve | s.e.